26min read

Already in 1954, after the publication of Max Hetzel’s Swiss patent for the later ‘Accutron‘ (Accuracy + Electronics) movement, the leading people at Omega realised, that electric watches would be part of the future of portable horology. Omega could not afford to be seen as an imitator of the Bulova watch company, for which the patent had been granted (1).

With no microelectronic competence, Omega, as part of the SSIH, began negotiations with the Battelle Institute in Geneva in 1955, for a collaboration in the development of an own electric wrist watch caliber. The collaborative project would be run by engineer Jakob Lüscher, leading scientist at the Battelle Institute (10).

1955 – 1964: Electromechanical Caliber Patent – Evaluation and Streamlining of Projects

The agreement was initiated in 1955 with the development of an electro-mechanical caliber for which patents have been filed, but ultimately only later prototypes (1964 – 1968) loosely based on the patent are known. Therefore, until 1957 the development of an electromechanical caliber remained inconclusive. Consequently an evaluation of all existing battery driven systems started in 1957. The meta-analysis run by the Battelle Institute would lead towards two possible systems with high potential: the confirmation of the legitimacy of the electromechanical system, by then researched by several manufacturers but with no potential for increase in precision, and the possibility of using a quartz regulator. Even if the use of a tuning fork system seemed more promising than the electromechanical system, the Accutron patent would impede the timely development of a better system (10).

The main goal of the agreement was to propel Omega towards the worldwide leadership of high precision watches, so by 1958 it emerged from the intensive studies around the electromechanical system, that the quartz system would form a far better basis to attain this goal. The engineers at Battelle would systematically look into the different components needed to run a quartz controlled watch. Then starting from 1959, the first 6 years of research were used to gather ideas and streamline the concept. It was clear that for a successful development of an electronically controlled quartz system of wrist watch size, the technology would be coming from the USA. Starting from 1960, Jakob Lüscher, the head of the project and Hans Hofbauer who was the technology expert, made several trips to IBM (International Business Machine Corporation) who was researching SLT (Solid Logic Technology) and RCA (Radio Corporation of America) who was researching MOS (Metal Oxide Semiconductor) system to learn about their advances. These technologies refer to the basics of the very first integrated circuits, which allowed to house several, functional, electronic elements into a very small space, while using a relatively small amount of energy to operate (10, 28, 29).

American Microelectronic Technology

The reason for the Swiss to go to the USA for learning about their electronic competence, was to take advantage of their technological advances. As the USA were hugely investing in space and military technology, consequently also the electronic developmental sector was booming, NASA and the military being the biggest contractors of the growing American electronics industry. NASA’s tight schedule and the need for small and lightweight devices for use in space further fuelled the research into miniaturisation of electronic devices.

Electronics research has been revolutionised by the work of Jean Hoerni, a Swiss engineer and cofounder of the microelectronics firm Fairchild in 1957. The details of Hoerni’s developments and their impact on the advances of microelectronics can be seen in this dedicated section, but what can be emphasised is, that it has later permitted the development and large scale production of miniaturised integrated circuits for watch movements.

The first integrated circuits were relatively slow, replaced only a handful of components, and sold for many times the price of their discrete transistor counterparts. This was the reason for the Swiss to either develop the technology themselves or use discrete elements. The former path was taken by Battelle and the CEH who later took Faselec on board to help developing their bipolar technology, the latter path was used by Longines to construct their cal.: 6512 which will be running the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ model (17).

1965: The Concretisation

While gathering expertise for creating the different components for the watch caliber, about 12 – 14 people were constantly working on Omega’s project of a quartz wrist watch movement. Lüscher had clear ideas about the construction of the quartz movement and stipulated that for the circuitry they would use and translate the American MOS technology, which crystallised as the most promising system. As for the rest of the circuitry they would only use discrete capacitors and transistors, as resistances would loose energy by heating up (10).

One, not negligible advantage for the Battelle Institute represented the fact of being an American institution, despite being located in Geneva. Thus, it’s engineers had unrestricted access to the American semiconductor technology. This has contributed to the fact, that the engineers at Battelle could use the brand new MOS technology and transfer the knowledge to their research application for developing an electronic wrist watch caliber without the need to apply for a time consuming governmental clearance procedure (19).

Lüscher wanted to develop an own version of the MOS integrated system and had his engineers order German silicon wafers to build them. By 1965, to simulate in big scale what would be constructed as a miniaturised integrated circuit, the team hand built simulators and a machine able to characterise the transistors and capacitors planned to be used (10).

Aspirine Shaped Quartz

In order to comply with the ambition of creating the most precise quartz system, Lüscher’s team turned towards a quartz crystal able to vibrate at 2.4MHz. Such crystals were produced only in England, by the company ITT, so engineer Jean Michel of Battelle traveled to the factory to supervise the manufacture and order the lentiform crystals of the size of an Aspirine pill (14mm diameter, 2.9mm thick). But the company ITT produced these lentiform quartzes only in a raw form. To optimise the quality and the regularity of the crystals, as needed by Battelle, the crystals were sent to Fort Myers, Florida USA, where they were packed into tubes filled with fine sand and then shaken following a specific protocol in order to roughen the surface (tumbling). The expertise to treat the crystals that way was only found in this small Floridian company, a subcontractor of the US Department of Defense (10, 19, 22).

The physical characteristics of a lentiform crystal permitted a high frequency vibration, which at that time couldn’t be attained with barrel shaped crystals as used for ‘Beta 21‘ or the Longines ‘Ultra-Quartz’ (10). The suspension of the quartz resonator would prove very difficult to achieve and would massively delay the manufacture of working prototypes. One can see tight parallels to the development of calibre Beta 21 and also Longines Ultra-Quartz, where industrial production was delayed because of very similar problems (10, 12).

1966 – 1968: Problems Arise

Much of the work done on the MOS integrated circuitry would be destined to be patented. Unfortunately for Lüscher, Texas Instruments and Fairchild, both pioneering electronics companies in the USA, would beat him for most of the patents, some by 14 days only. Despite the patents, the great ideas and theoretical work done by the Battelle engineers, no working prototype could be presented by 1967 (10).

With the high frequency vibration of the crystal, also the energy consumption to stimulate, control the crystal and for frequency division would increase. There Lüscher’s team thought of a trick to circumvent the high energy consumption by using a resonance circuit in which the necessary frequency division would be integrated. They did so by introducing two ferrite coils, each vibrating at 400KHz which would be synchronised with the crystal vibrations and which would take over the first crucial frequency division (x6). The remaining frequency division from 400KHz down would be attained with 16 binary sub-stages to 1 Hz to run the stepping motor. If taking these developments on larger scale, one recognises that Longines independently followed a similar path of ‘cybernetic’, self regulating synchronisation simultaneously for the development of their ‘Ultra-Quartz’ model (1, 10)!

The layout of the movement, the engineering of the single components and the electronic solutions provided by the engineers sounded great in theory, but especially the frequency division from 400KHz down to the 1Hz of the stepping motor proved impossible to achieve (10).

By 1967 Omega had invested the big part of 15 Million Swiss Francs for the project (= 150 Millions in 2023), and being shareholder of the CEH, Omega witnessed the revolutionary developments at the CEH creating the worlds first quartz wrist watch caliber in July 1967: Beta 1 (19).

At that crucial time point, to have the project advancing faster, the technical director at Omega, Hans Widmer, imposed Lüscher to collaborate with Intersil, a new integrated circuit manufacturer in the USA, founded by the Swiss semiconductor pioneer Jean Hoerni after leaving Fairchild. Omega was minority shareholder of Intersil, a status which would facilitate the collaboration. Intersil would be located at the exact spot in Cupertino (CA), where Apple computers has its headquarters nowadays. As mentioned in this dedicated section, Hoerni invented an important procedure (planar process) for creating integrated circuitry on silicon wafers. Despite the dissatisfaction of the Battelle Institute, Hoerni joined the project as a consultant. Not only Intersil was recruited to speed up the process also Faselec – CEH, separately working on the development of a bipolar integrated circuit module (without using the energy saving MOS technology) for the commercial version of their Beta 2 prototype (future Beta 21) movement joined the efforts as contractors (19).

1969: Finalisation of the 2.4MHz High Frequency Project

With the help of this interdisciplinary and international, electronics network, the project could be finalised by 1969. In the meantime, in 1968 Peter Döme of Battelle will invent the motor, which will be patented (# 583.929), but the actual development and refinement for the production caliber will be made later by Omega’s engineer Willy Cleusix. Latter engineer was part of the team of John Othenin-Girard and Bruno Erni, which through intensive exchanges with Battelle made sure, that the knowledge about the developments finally converged to Omega’s dedicated R & D department. The first working prototypes using, what will be later designated as cal.: 1500, were presented during the International Chronometer Congress in Paris held the 16th – 19th of September 1969 (1, 10, 12).

The Elephant

A few months later more elaborately cased prototypes were presented at the Basle fair of 1970, at the same time as the presentation of the Beta 21 system and Longines ‘Ultra-Quartz’. These elaborate prototypes with enormous cases were nicknamed ‘Elephant’ or ‘Mickey Mouse’. The designation ‘Elephant’ was the internal codename of the high frequency project at Omega. Cal.: 1500 was run by two batteries for the needed 2.7V of tension, the protrusions of the two battery housings induced the nickname ‘Mickey Mouse’. The Omega marketing department also was ready with the model name for the new watch: ‘Megaquartz’ (1, 24).

Cal.: 1500

As mentioned before, the first working prototypes were running with cal.: 1500, where all of the above mentioned technology could be integrated. Referring to the picture above, the upper two circular bulks would be housing the two miniature batteries. These two bulks would be responsible for the nick name ‘Mickey Mouse’ given to this type of prototype.

On the lower left, one can admire the location of the big circular quartz, mostly covered by the integrated circuit (gold coloured, named CHO-2 IC, developed by Battelle in collaboration with Jean Hoerni using MOS technology) and the brass circular trimmer. On the lower right two smaller, circular, dark grey protrusions designate the position of the two ferrite elements which vibrate at 400Hz and the resonator circuitry. Between the several circular elements and the golden coloured integrated circuit the engineers had to position the mechanical parts not yet including the date mechanism, which will be added later. Between the circular quartz and the left battery housing one can see the two rectangular metallic blocks belonging to the motor.

1970: End of Collaboration with Batelle and Intersil

With the construction of cal.: 1500 and the presentation of the system at the Basle Fair in April 1970, the collaboration between Battelle and Omega definitively ended. The overlap of the final technology transfer began with the end of the contract between Batelle and Omega which is dated 1.7.1969. Also the collaboration with Jean Hoerni ended in 1969. From then on Omega took over the refinements, while the further miniaturisation of the electronic system was contracted to the CEH, who would create the commercial movement version, cal.: 1510 (10, 12).

Cal.: 1510 and Derivates

For the technology transfer and development of the commercial version of cal.: 1500, Omega turned to the expertise in microelectronics of the CEH. While having profited from the collaboration with Battelle and Intersil to finalise their cal.: 1500 using the MOS technology in their CHO-2 IC, now the contract with Battelle having expired, the relationship with Intersil having experienced some troubles by 1969, the collaboration with the CEH had to be intensified (24).

CEH engineers tackled the planning of the next generation of IC for the future, marketable ‘Megaquartz’ model. After several years of work the new CHO-3 IC now integrates already the very advanced CMOS technology developed at the CEH, making the Omega ‘Megaquartz 2.4MHz’ one of the first quartz watches integrating this technology. This revolutionary CHO-3 IC, by integrating the CMOS technology, would have enormous influence on the further development of the definitive caliber. For one, the frequency division would be possible using binary dividers, all integrated in the IC, instead of using the experimental 400Hz ferrite, resonance circuitry of cal.: 1500, saving space and allowing for a smaller caliber.

The energy saving properties of the CMOS technology would allow for adding more electronic and mechanical features to the movement, such as the TSA-System and a date mechanism. By consequence, the reduced power consumption was even allowing to use only one battery (11, 23, 24).

The Motor

The motor belongs to the class of electrodynamic stepping motors, a variant already used in the CEH prototype Beta 1 in 1967. Internal experiments at Omega had shown, that this motor has a functional reliability of at least 99.99999%. This type of motor will get standard in quartz watches, showing the well known step-wise progression of the seconds hand. Vibrating motors as used in Beta 2, Beta 21 and in the Longines ‘Ultra-Quartz’ model contained elements (specifically: index fingers), which were prone to get easily damaged and thus such motors were very difficult to repair and adjust and went out of fashion quite quickly (23).

Date and TSA-System

However, one other main problem encountered during the development of the definitive calibre was the date mechanism, which usually would drain a lot of energy (500% of what the motor can provide). The use of low consumption CMOS in the IC of cal.: 1510 has not only permitted to reduce the battery consumption as compared to cal.: 1500 (1 battery instead of 2), but has freed enough energy, to allow for the integration of a date mechanism. Jakob Lüscher and his team at Battelle had previously invented an ingenious, low energy demanding system, still in use today (1, 10).

The commercial cal.: 1510 was also equipped with a mechanism to enable the hour to be changed independently of minutes and seconds along with a separate pusher for setting seconds: TSA (Time Second Adjustment). Thereby allowing extremely accurate time signal synchronisations (4). This system works electronically by influencing the motor with added or blocked energy pulses and is not a pure mechanical feature (23). This revolutionary system for time-setting has been developed by Omega’s Pierre-Luc Gagnebin and will be integrated in many electronic Omega models until the early 1980s (12). Another feature had to be integrated directly into the CHO-3 IC, more specifically inside the last 5 binary divider steps, allowing for an electronic ‘hacking’ mechanism for the seconds hand, the first of its type in a wrist watch (23).

No Thermocompensation

As this development was targeting absolute precision, it would be logical to introduce a thermo-compensating system, allowing for the precision not to vary in dependance of temperature variations. Actually, the fact of using a high frequency quartz renders a thermo-compensation obsolete, as these quartzes, if cut the right way (AT-cut: 35° to longitudinal axis) show a four times lower frequency variation than low frequency quartzes (< 1MHz) and a constant, stable frequency between 20°C and 40°C with neglectable variations around these marks (23).

Constellation ‘Megaquartz’ and ‘Marine Chronometer‘

Around 1971/72, before the official production of the Megaquartz models, there were several intermediary steps such as transitional 1500-1510 calibers (P2) for testing the new CHO-3 IC with CMOS technology and later about 10 prototypes (P3) with truncated, pyramidal shaped cases were made and allegedly given to high ranking employees for functional testing of the finalised cal.: 1510 (4).

The technology transfer from cal.: 1500 to cal.: 1510 and the development of the industrial calibers and the corresponding watches took almost three years, culminating in the introduction of the models ‘Constellation Megaquartz 2.4MHz’ with cal.: 1510 in early 1973 and the model ‘Marine Chronometer 2.4MHz’ with cal.: 1511, and cal.: 1516 introduced in 1974 and 1976 respectively (2).

The used calibres still being of quite big size and almost square, demanded for a voluminous casing. Although not comparable with the unpractical design of the ‘Elephant’ prototype, the early marketed models were rather big in size and feature either an integrated bracelet or a leather strap with deployment buckle (1,4).

Marine Chronometer Certification

The special shape of the calibre ensures that the limit of 707 mm2 set by the Neuchâtel Observatory for wristwatch chronometers is not exceeded. This was not a problem as long as only standard chronometer certifications for cal.: 1510 (1973) and cal.: 1515 (1973, not commercialised) were requested. Everything will change in 1974 once marine chronometer bulletins are requested for cal.: 1511. There will be only two of these bulletins, in total and for all. The Observatory in Neuchâtel immediately changed its regulations, so that only watches with a dial of least 60 mm in diameter could be adorned with this supreme title. As a result, the Omega ‘Marine Chronometer’ with its 24 mm dial was disqualified. Omega had to have all its other timepieces homologated as marine chronometers by the Observatory in Besançon in France. (12)

Aftermath

When the Megaquartz equipped with the cal.: 1510 finally came onto the market in 1973, the prices for conventional quartz watches with 32kHz resonator, digital CMOS division to 1Hz and Lavet-stepping motor were already massively falling. The production of the standard model remained very modest at about 1000 pieces. In 1974, the first edition of about 900 ‘Marine Chronometers’, certified at the observatory in Besançon, with cal.: 1511 was produced, followed two years later by a second edition of 1800 with cal.: 1516. The production of the ‘Megaquartz 2.4MHz’ was discontinued in 1975/76 (1, 4). Nevertheless, the Omega ‘Megaquartz 2.4MHz’ remains to date the most precise non-thermocompensated wrist watch and the smallest marine chronometer ever made (12, 23).

4.2MHz: The High Frequency Journey is Not Over

Omega had mandated the CEH to optimise cals.: 1510, 1511, 1516 which were to be discontinued, to create the successor cal.: 1310 with a more standard 32KHz. In January 1974 CEH-engineer Henry Oguey started with the analysis of all generations of Omega CHO-IC’s, also the ones made by Battelle, for the ‘Megaquartz’ model, starting with general analyses, experimental CHO-1, then CHO-2, which was mounted inside the ‘Elephant’ prototypes of 1969. The circuitry analysis moved on to CHO-3 used inside cals.: 1510, 1511 and 1516 running the commercialised 2.4MHz ‘Megaquartz’ and ‘Marine Chronometer’ models (21, 24).

Coup Bas

However, 1975 a big coup was made by Citizen, which launched their ‘Crystron 4 Mega’ model with the 4.19MHz cal.: 8650A. This was a massive step up in accuracy and the watch had a rated accuracy of ±3 seconds per year. This accuracy came at cost with the first ‘4 Mega’ model priced at ¥4,500,000. The watch was housed in an 18K yellow gold case, bracelet and crown, with an octagonal sapphire crystal (26).

While globally the prices for quartz watches continued to decrease and the ‘Megaquartz 2.4MHz’ was destined to be discontinued, the advancing of the integrated circuit technology permitted to use lower consumption components not available before. To regain the supremacy of high frequency quartz wrist watches, Omega decided to invest into the development of their own 4.2MHz version they wanted to baptise ‘Megaquartz f 4.2 MHz’, giving it the reference ST 398.0851, on the basis of reference 198.0116 (20, 25).

Further Integrated Circuitry development at the CEH for Omega

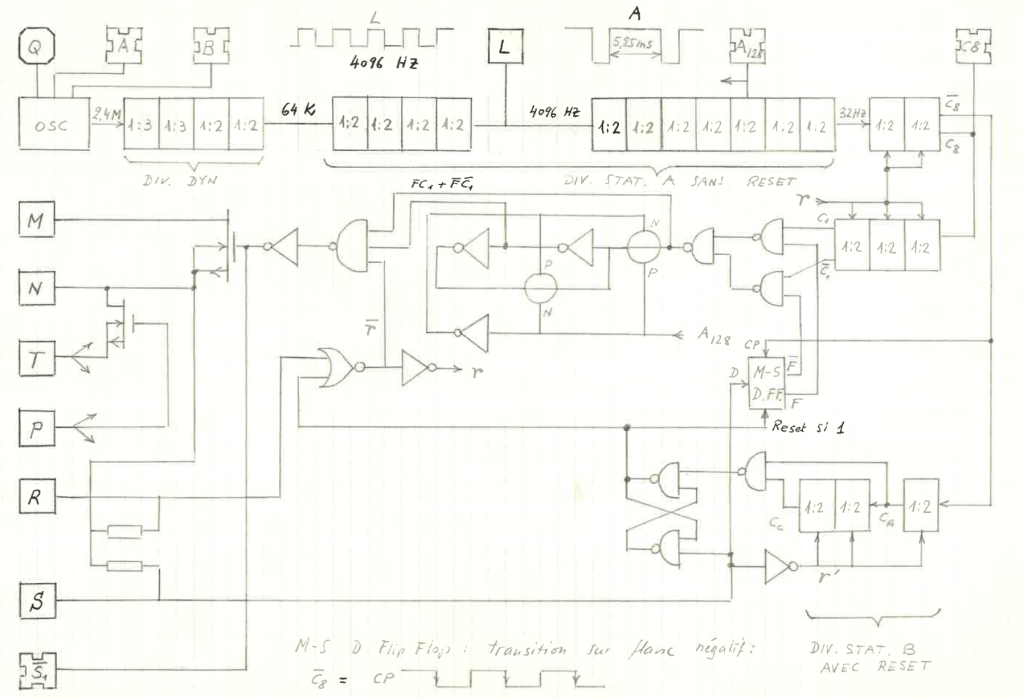

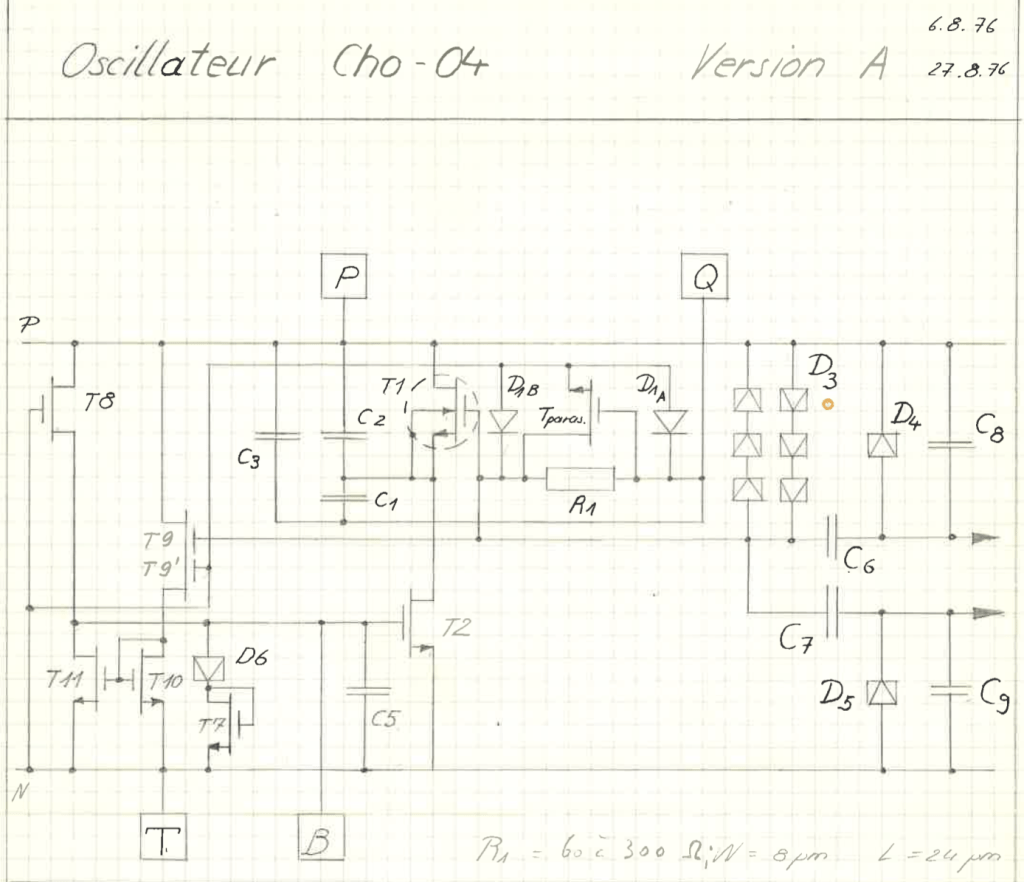

The news about the high frequency Citizen watch would force Omega to launch ‘Project 1.13’, again in collaboration with the CEH in Neuchâtel. Even with the advancement of technology permitting to construct smaller and more precise quartz movements, this new project, developing a 4.2MHz watch, would bring the engineers again to the edge of known physics. Fortunately the CEH had already worked on the optimisations of the CHO-3 circuitry of cal.: 1510 for the new cal.: 1310, see above. So ‘Project 1.13’, as a sideline of the project optimising cal.: 1510, would result in the creation of CHO-4, which would be the IC for the new 4.2MHz development. The first technical description of this CHO-4 and the mentioning of a circuitry for a 4MHz watch dates from 6.8.1976 (24).

The advantage of creating a quartz watch with the highest possible quartz frequency is, besides the increased precision, the reduction in size of the quartz-module. However, a quartz with higher oscillation frequency needs more dividers and thus a circuitry which drains more energy, so the development of the corresponding IC would need to take this problem into account. By 1976 the technology was permitting the use of CMOS technology almost in a standardised way, but the more complex an IC was constructed, the higher the failure rate in production of these IC’s. The 4.2MHz quartz wrist watch compatible CHO-4 IC, which integrates 21 binary frequency dividers amongst numerous other components, was extremely difficult to manufacture (19).

Omega realised a few prototypes by taking their in house quartz cal.: 1342 (a derivate of cal.: 1310 developed by the CEH), equipping it with a high frequency, barrel or rather tuning fork shaped 4.2MHz quartz module and adapting the control and frequency division circuitry by integrating the CHO-4 IC, developed at the CEH. The project had proven scientifically successful and a hand full of such experimental 4.2MHz movements were made, all discretely housed inside commercially available cases with corresponding dials not revealing the technology hidden underneath, some even marked ‘Automatic’. One of the known prototypes shows the caliber attribution: 1522. As this high frequency wrist watch was not commercialised, the caliber number has been re-attributed later (2, 20). Despite all efforts, the IC was difficult to manufacture and the caliber was still very energy consuming, so the project was definitively shelved the 19.11.1980, but the high frequency experiment would not have been in vain (20).

Boxed Marine ‘Ship’ Chronometer

In 1978 the French Naval Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service (Service Hydrographique et Océanographique de la Marine or SHOM) requested a Quartz Ships Chronometer to acquire a reliable autonomous time source independent of external satellite and radio signals. The goal was a timepiece for navigational purposes. Thirty-six watch and clock companies applied (2).

With cal.:1522 of 1977 as a basis, a Quartz Marine Chronometer clock movement (cal.: 1525) was designed with a high-frequency 4.19 MHz quartz oscillator that should be capable of an accuracy of approximately ± 0.01 second/day. the IC used was the successor of the one used in the wrist watch prototypes and named CHO-5, also developed by the CEH (24). Omega’s entry used the new cal.: 1525 movement giving an accuracy of less than 5 seconds per year and was selected after a year of testing at sea by the French Navy Hydrographic and Oceanographic service. The timepiece was also tested by the Neuchatel Observatory under rigorous conditions: temperature variations, thermal shocks, magnetic and electric fields, mechanical vibrations etc., which after 47 days of examination earned the official quartz ‘Quartz Marine Chronometer’ certificate. This is a higher standard than the mechanical Marine Chronometer by which standards the 1974 wrist Marine Chronometer was tested. The ships clock featured an external electronic connection “1Hz – 1 V”, an electronic switch to stop the movement or operate at normal or double rate (the second hand advancing in ½ second increments for optimal timing of celestial objects angle measurements) with a locking knob to prevent accidental actions, power reserve switch with power indicator to check the battery condition, and a frequency regulator (2).

The clock came commercially on the market in 1980 as the Omega ‘Megaquartz Marine Chronometer’ at great expense, but was predominantly used for military application with the French Navy, which used the Marine Chronometer clock in the majority of their fleet. About 2000 Marine Chronometer clocks were made, and about 1000 were used by the french Navy (20). By that time, bearings could be taken by means of satellite navigation. Nevertheless, French Navy regulations still required an independently operated timepiece on board so that, in combination with a sextant, the ship’s position could be determined by celestial navigation (2).

Post Scriptum:

This entry is dedicated to Thomas Dick, a very knowledgeable Omega collector, who was lover and expert of specifically ‘Megaquartz 2,4MHz’ prototypes and production models. He knew Omega engineer John Othenin-Girard personally, gained an enormous amount of knowledge over the years and wrote numerous articles on watch forums and the Wikipedia entries for these watches and for the Omega ‘Electroquartz’ models. Many prototypes of these Omega models were researched and described the first time by Tom. He left us too soon and he will be dearly missed.

Ref.:

- Trueb L. F., Ramm G., Wenzig P.; Die Elektrifizierung der Armbanduhr; Ebner Verlag, 2011

- Omega Marine Chronometer; Wikipedia, by Thomas Dick, @retromega1977

- Richon M; Reise durch die Zeit; Omega SA, 2007

- Omega Megaquartz, by @t_solo_t

- Antiquorum

- The Battelle Institute, Geneva. Nature 205, 238 (1965).

- Invent.org

- Leuenberger F., Vittoz E.; Complementary-MOS low-power low-voltage integrated binary counter, Proceedings of the IEEE, Vol. 57, NO. 9, 9.1969

- Piguet Ch.; Integrated Circuit Design Power and Timing Modeling, Optimization and Simulation 12th International Workshop, PATMOS 2002 Seville, Spain, September 11-13, 2002, B. Hochet, A. J. Acosta, M. J. Bellido (Eds.), Springer

- Personal archive of an Engineer who had worked on the Project at the Battelle Institute since the beginning and was the right hand to Jakob Lüscher, head of the project at Battelle

- Personal communication with an engineer who worked for Omega on the technology transfer from cal.: 1500 to cal.: 1510 (after the end of the contract with the Battelle institute) and the development of cals.: 1510, 1511 and 1516.

- Richon M., Die Omega Saga, Omega SA, 1998

- AISOR

- Computerhistory.org – 1959

- Electronics Tutorial

- Tutorialspoint

- Computerhistory.org – 1962

- The Transistor Museum

- Personal communication with a former Executive Vice-President of Ebauches SA, in charge of Research & Engineering

- Richon M. for SAMO-Bienne

- CEH-Archives at the MIH

- Written correspondence between CEH and Omega, 20.9.1975

- J. – P. Jaunin (Omega), Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Forschung und Technik, 8.4.1974

- Technical reports of the CEH for Omega’s Megaquartz model

- File preceding the estimated launch of the 4.2MHz model, 17.02.1978

- Plus9Time

- @retromega1977

- A Brief History of the MOS transistor – Part 4

- A Brief History of the MOS transistor – Part 5